seeing like a screwdriver

what counts as information?

I, somewhat foolishly, got into an argument on social media last week with someone over the slogan “POSIWID” (the purpose of a system is what it does). This is often held up as a central theorem of management cybernetics - in fact it’s a bit of an afterthought, first appearing in “Diagnosing the System” which was one of Stafford Beer’s minor works, a guide to his model for operating managers. But “someone who was wrong on the internet” objected to its use, saying that it was conspiratorial and unfair and that instead we should talk about unintended consequences a lot more.

I have little time for this; for one thing, the whole point of the slogan is that we can’t tell from the outside whether something was unintended or not. And for another, “unintended consequences” is all too often a first cousin to “perverse incentives”, which is a synonym for “doing something you know to be wrong, because you want the money or other rewards you get from doing it”. And so ensued a predictably unproductive argument set of exchanges, all of which were shaped by the fact that we have to talk about systems in our everyday language, which doesn’t have a vocabulary particularly well suited to doing so.

Consequently, I thought that “the purpose of a screwdriver is to drive screws” was a reasonably straightforward sentence, demonstrating that attributing a purpose to something doesn’t involve anything like a conscious belief1. Other people insisted that any such statement has to be unpacked into statements about intentions. It didn’t really go very far.

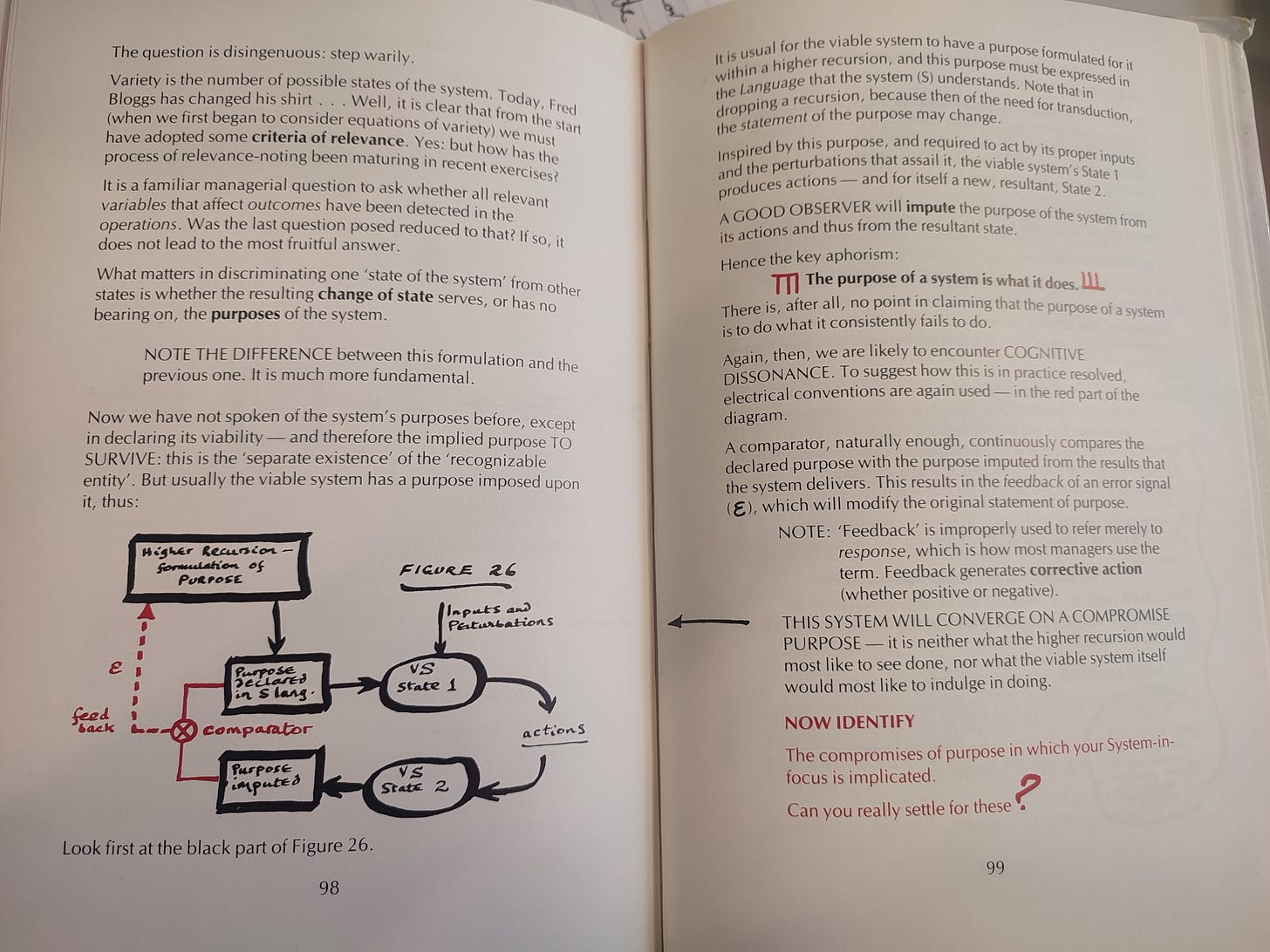

So I thought I’d go back to Stafford Beer to look at the context in which the original aphorism was coined. Here it is, from p98 of “Diagnosing the System”:

These are two very information-dense pages, making use of a lot of technical language from the previous ninety-seven. The “disingenuous” question referred to at the start is effectively the question of “whether the system is capable of handling all the information produced by its environment”.

So the context here is a very important point which distinguishes cybernetics from information theory; the distinction between “information” (something that plays a causal role in a decision making system) and “data” (assemblages of facts and sequences of bits). The question of “purpose” arises precisely because this is how you decide what constitutes a relevantly different state of the world.

And the question of “relevantly different state of the world” is determined at a number of levels. The system you’re looking at might have its own purposes (to drive screws). But it might be embedded in a larger system (say, a prison) in which pointed metal objects have other purposes. And in many cases, along with its idiosyncratic purpose, the system has an overwhelming drive to stay in existence as a system. As Beer points out, the behaviour of any actually existing system is going to be a compromise between lots of different drives.

As I say in the book, it’s easy to mistake POSIWID for a much cruder, “it is what it is” kind of cynicism. It’s actually a much deeper concept in my view. The purpose of a system is exactly what is being worked out every day, as that system reproduces and maintains itself, decides what events it is going to react to and how it is going to balance present interests and future possibilities. And so the doing of things is, identically, the creation of purpose. A screwdriver which just lies around in a drawer doesn’t have any purpose at all2.

Or does it? I’ve got a screwdriver which does exactly that, but its purpose was to make me feel a bit better about some otherwise annoying consultancy work I was doing.

The purpose of some screwdrivers is to screw around.

Ooh, interesting question, if you regularly use a screwdriver to lever something open because what you need is a strong piece of metal with a wedge at the end, is that the purpose of a screwdriver?