wisdom of the amoeba

Beer tasting notes, part 2

Another in my occasional series focusing on difficult or easily misunderstood concepts in the management philosophy of Stafford Beer. This week, I look at “System 4”, often called “Intelligence”. It’s the part of the system that’s meant to deal with external factors other than those in the “immediate environment”. To a large extent, System 4 is what makes the Viable System viable, in the technical sense of “able to survive shocks which were not anticipated at the time of its design”.

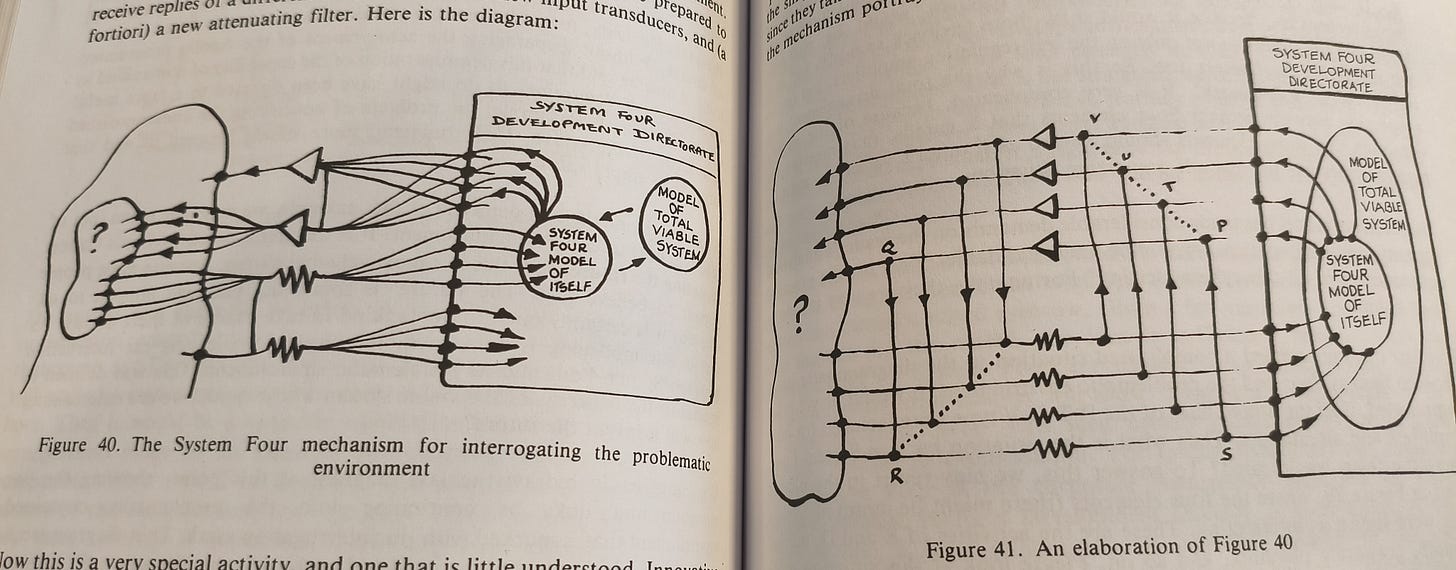

It’s a tricky business. Look at this diagram, I mean bloody look at it:

And it feels like this part of the Viable System Model shouldn’t really be so difficult to understand – isn’t System Four just like market research, or R&D, or something? Unfortunately not, because by this point in Beer’s system, we’re very committed to his understanding of “information” as necessarily being something with a causal connection to action and decision making.

That causal connection becomes a bigger cybernetic exercise when the decision making system gets bigger and more complicated. As Beer says in The Heart of Enterprise:

“Dealing with the Outside and Then in the traditional enterprise (whether public or private) was a simple matter – before the Second World War. The boss was primarily occupied with the stability of the internal environment. And rightly so. He could deal with the problems of System Four in the bath

[...]

But of course, the boss has (rightly) been taught to delegate ... the System Four function to various and disconnected teams of ‘advisors’. This was an option apparently open ti him, because of the definition between ‘line’ and ‘staff’ management that became established after the Second World War, when military usage in the matter was embraced by civil management. It had worked well in the armed forces; it worked well, for perhaps twenty years, in business and industry. It works no longer, and I think it should be abandoned”

What he’s on about here is that we’ve had two steps where reorganisation was needed. First, when the problems of System Four became sufficiently complicated that they could no longer be held in one person’s head. And second, when they grew sufficiently complicated that they couldn’t be handled by “one person with a team of advisors’ eiither. The business of trying to ensure adaptation now needs to be institutionalised in the same way that physical manufacturing has been. And that means that, as in the Industrial Revolution, effort needs to be made in breaking down the analytical process into tasks and systematising them so that they can be industrialised.

“Adaptation” is the mot juste here – the title of this post comes from Beer’s point in Heart that evolution is nature’s System Four. You can match your variety to that of a really complicated and changing environment simply by making lots of slightly different copies of yourself and seeing which ones survive. As he says, “this is probably why the coelcanth is still with us while Rolls-Royce has gone bankrupt”. But as he also says, this isn’t a particularly useful strategy for most organisations; you wouldn’t even really want to try it out on your own family.

So the alternative approach is simulation – System Four has to have an implicit model of the whole system, because what it’s interested in is not outside information per se, but rather the potential effect of outside developments on the system. That’s part of the point of the diagrams above.

The real issue that those diagrams are meant to be illustrating, though, is that System Four has to break out of the mental prison. If it’s only looking at, projecting and simulating things which are captured by the existing reporting systems (which is more or less exactly what “stress tests” in the financial sector always do), then it isn’t really dealing with Outside and Then at all. It needs to interact with the “problematic environment”, the blob with a question mark in the diagrams. (In my book, I suggest that this was the story of the financial crisis; the mortgage debt bubble just wasn’t contained within the space of possible risks for the central banks, and although they thought they were constantly forecasting and looking at risks, they were stuck in a specific finite domain).

Interact how? That’s the purpose of the weird arrows. In order to really simulate unanticipated shocks, System Four has to be constantly trying to “know what it doesn’t know”. In order to do this, it has to be designing the reporting and information gathering systems themselves, putting out experiments, getting the results back and building feedback loops to redesign.

All of which goes to explain why “missing or inadequate System Four” is such a common driver of organisational failure. It’s really bloody difficult to think outside the box, and a lot of the time it just gives you bad news anyway.

As an ex-futurist (outside consultant) yes it is very hard, but it’s also grimly apparent that businesses don’t like spending effort/resources/money on it. Obviously hard to prove, but it does seem like it would be worth trying.

I was thinking about Beer and your book again after listening to Abundance, the Klein/Thomson book. I enjoyed the political criticism part and was left feeling that we need some kind of higher level political reasoning/debating system that can help solve the failures produced by conflicting complex overlapping interests and the issue that sort of loudness of voice doesn’t always or even only rarely maps onto weight of interest (by like democratic weight or something I mean). It would be good if this were not a technocratic or strongman leadership thing but something that managed to actually measure and engage all people’s interests. (I’m immediately falling down a hole by failing to define “all people” but I guess at least it ought to relate to a nation, although I can feel an argument with my self coming on already.)

Anyway, maybe you’ll write about this sometime and tell me the answer! 😃