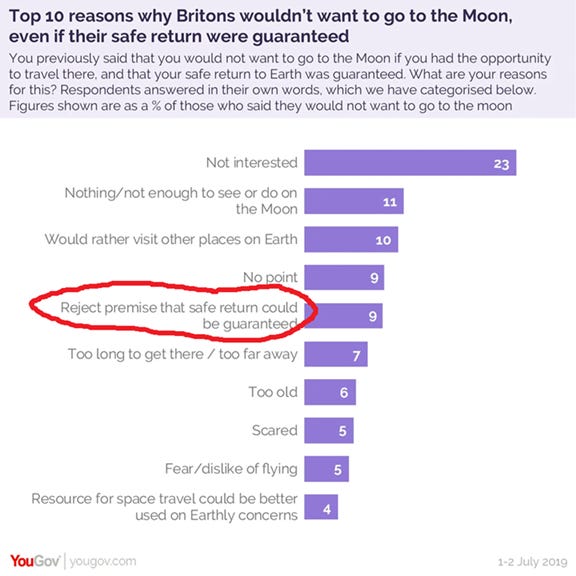

reject premise that safe return could be guaranteed

information environments are made, not found

I know that it’s a minority of a minority, but graphics like this give me some hope that common sense is not quite dead.

That 9% are my people.

It is not possible to get away from hypothetical questions entirely, but whenever you’re asked to consider one, it is a good idea to think about what restrictions have been put on your information environment, and whether they’re just natural consequences of the fact you don’t have infinite capacity, structural information gaps that everyone has, or sneaky little hacks that someone has put in to steer you toward the right answer. As Kevin Munger says in a great post this week on the general topic of how difficult it is to think about systems as systems:

Imagine any popular ethical thought experiment. It involves some actor in a situation with some well-defined entities. You’re walking alongside a river, there’s a drowning child, and you are wearing a fancy suit. The ethical decision about whether to save the child hinges on how fancy your suit is, your estimate of the physiognomy of the child (he looks like he might be >95th percentile criminality :-/ ) and your monetary discount rate divided by your timeline for AI X-risk…

All of those parameters are fascinating, for a certain type of person, but before you pull out your calculators and start multiplying probabilities by consequent utiles, take a second to recall that the medium (of the thought experiment) is the message: the message is that the world consists of entities like “suits” and “rivers,” that a few sentences are sufficient to define a human’s experience of the world, and that those humans have an essentially unlimited amount of time to perform those calculations.

I was always horrible at dealing with these kinds of thought experiments - it was only much later that I had the toolkit to understand that the answer I was groping for was “the reason that this seems like a dilemma, or that the utilitarian answer seems weird or repulsive or underjustified, is that the weirdness has been built into the example, because it is describing a strange and impossible information environment that nobody could ever actually be in, so why should we expect our moral intuitions to give us good or satisfying answers here”.

In economics and finance, we have lots of lovely things called “separation theorems”. These are often really important, because they are proofs that, for example, the decision about whether to make an investment or not can be separated from the decision about how to finance it. (You can’t make a bad idea good, or vice versa, by changing the amount of debt you use). I think the concept of a separation theorem is there in the background in a lot of ethical and political reasoning. (It’s definitely in the background of a lot of the current debate about Abundance and Everythingism, or in all the calls for builders to be building rather than worrying about bats and fish discos and the like).

The trouble is that the same maths which establishes separation theorems tends to show that it’s a really bad idea to pretend that you’ve got one when you haven’t. And the way that economics establishes its separation theorems is specifically to play games with the information environment; to exclude everything from the objective function that might mess up the proof. This might almost be definitional of the subject - economists are specifically those social and political scientists and philosophers who are given permission to ignore things that might get in the way of the output goal they have chosen to set.

But it turns into a problem when moral philosophers, political theorists, sociologists, urban geographers, etc get their heads turned by how easy the economists have it and try to (loosely speaking) help themselves to separation theorems while trying to also enjoy the benefits of acting like they’re talking about the real world in which things are hard to separate.

I’m still preparing for my review essay of Abundance (which might also have to incorporate Breakneck, now that it’s published and I no longer have to grit my teeth hearing my mates who got advance copies say how great it is). And I think I might need to base it around last week’s “Everything Bagel” joke - that an everything bagel is a bagel which has everything appropriate to put on a bagel rather than absolutely everything. Dealing with wicked problems by trying to unpick them via separation theorems is an excellent method and economists have done well by it. But that means that most of our remaining wicked problems are not amenable to this approach - particularly in cities, lots of important things really are connected in complicated ways - and there’s a grave danger in trying to un-wicked them by just saying “nuh uh. not wicked. no need to think about that actually”.

The discussion of hypothetical questions reminds me of John Holbo's great posts about thought experiments in Philosophy.

https://crookedtimber.org/2012/02/25/occams-phaser/

https://crookedtimber.org/2013/11/30/laugh-if-you-like-but-death-on-the-tracks-is-funny/

"The genre of the analytic philosophy (Anglo-American, call it what you like) thought-experiment is a mildly humoristic one, in that it tends to Rube Goldbergism. Of course the point is always to solve for variables! You never tie another victim to the tracks, or fatten one up, for any other reason than that he/she is strictly needed in that place or shape. Nevertheless, the more outlandish the set-up gets, the funnier it gets. And I think it’s fair to say that philosophers quietly award themselves style points for (plausibly deniable!) whimsy, above and beyond conceptual substance.

The problem with that, I should think, is that mirth is an emotion that may affect our moral thinking. Specifically, it makes us more utilitarian. See this more recent article as well [sorry, Elsevier paywall]. The trolley scenarios are, or may be, used as intuition pumps for utilitarian purposes. (They may be used for other things, of course.) But it is an underdiscussed fact that they may inherently do so, in part, because trolley tragedies can’t help being a bit funny."

https://crookedtimber.org/2019/12/16/whimsy-analysis-alienation-between-wodehouse-and-brecht/

"The issue is this: whimsy is – well, it’s not an emotion, I don’t suppose. It’s an attitude. More exactly, it’s a mode or manner of being detached. But it’s not a full, nor neutral style of detachment. It’s not the view from nowhere. It’s not action-oriented. But that doesn’t make it pan-observant or unfeeling. It’s perpetually tickled; it’s preferentially attendant to certain things, as opposed to others. (It knows you can’t just tickle yourself. Something else has to do it.)

The concern is that this makes it stupid, not to put too fine a point on it.

..."

Reminiscent of an old question that Abraham Lincoln used to pose.

"How many legs does a cow have, if we agree to call the tail a leg?" Answer: four, because calling a tail a leg doesn't make it so.

And unlike most of Lincoln's best "quotes," he really did say this.

https://timpanogos.blog/2007/05/23/lincoln-quote-sourced-calfs-tail-not-dogs-tail/