oscillations and arguments

Beer tasting notes, episode 4

(an occasional series on details and insights in the works of Stafford Beer. Previous episodes, one, two, three and one that I did before coming up with the series title. If you aren’t interested in management theory and cybernetics, do feel free to skip this one).

Held over from last week, this is my promised analysis of the “SYDN” anecdote in terms of Stafford Beer’s “Viable Systems Model”. It’s all, in my view, about the greatly misunderstood “System 2 – Regulation/Coordination”.

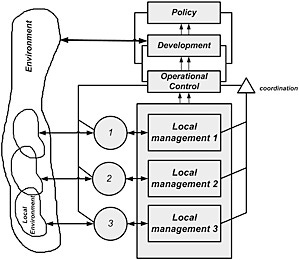

Bringing everyone up to speed on this part of the VSM, System 1 is “Operations”, the part of the system that interacts with the outside world (and therefore, is capable of independent existence, and therefore, has to have its own internal replication of the five subsystems that determine viability). People (including me) often talk about this as a single subsystem, but in fact Beer makes a big point of saying that if you think you’ve found an organisation that only has one System 1, you’ve almost certainly not analysed it thoroughly enough. There wouldn’t be an interesting problem of management if everyone only did one thing.

So there are usually lots of different and discrete Operations subsystems – in the case of the brokerage firm I was describing, each sales team and each research team was serving clients. And when this happens, a lot of organisational energy has to be expended in managing the interactions between the different operations. In particular, they will usually have competing demands on resources. For example, the sales desk wants to use the time and labour of the research department; this was by no means the most important such conflict, but it was significant enough to cause problems. There are two ways in which these conflicts are handled.

One of them is the “resource bargain”, a key part of the system. The underlying idea here is that it is most efficient to push decisions down to the lowest level at which they can be made, because communication (and particularly, communication between different levels) is expensive and wasteful. So each little circle on the diagram gets told “you can make your own decisions, as long as you do not consume resources in a way that harms the rest of the organisation”. Defining what constitutes “harming the rest of the organisation” is the key responsibility of System 3 (Optimisation), which is the level of management that is meant to draw up and administer the resource bargain.

But between 1 and 3 lies another important subsystem, which Beer calls “regulation”. The canonical example of such a system is the timetable for a school, which prevents two teachers from trying to use the same resource of physical space (ie, classroom) at the same time. The regulatory system is distinct from the resource bargain because it’s meant to operate without decision-making. It prevents “oscillation” – which is to say, not the practice of squabbling over resources, but the inevitable causal consequences of what would happen if one team relies on using a resource which isn’t there because someone else got it, then tries to adapt to its absence, which causes another team which was relying on it to have a problem.

The distinction is quite subtle and confusing. Beer noted that in his consulting work, it very often happened (but rarely vice versa) that people in System 3 identified their jobs as System 2. Of course, that’s all about accountability – System 3 makes decisions and sets priorities, while System 2 is just helpful admin and record keeping to ensure the metaphorical factory floor is tidy.

So what about the “Trade Fair”, the planning and allocation exercise that I subverted with the masterly “say yes, do nothing” strategy? Looking back with the benefit of a bit of management cybernetics, it’s clear to me that this was a misdesigned System 2. It took the form of a resource bargain, but it wasn’t one; a true resource bargain would have needed to be set by management, and they correctly realised that they weren’t in a position to impose one. (They were in a good position to supervise the resource bargain worked out informally, and often did so by coming round to team heads and saying “I notice you guys haven’t been to Benelux for a while” or some such).

So it wasn’t a resource bargain, it was an attempt at a System 2 regulatory system to mitigate the knock-on consequences of marketing trips for everyone else’s workflow. But it couldn’t work as such, because of another important principle of organisation – the fact that all the constraints need to be satisfied in time. The real weakness of the thing was that it was an annual planning exercise, for a business which changed a lot from month to month. That was what made it useless for its purpose, and such a source of bad feeling between people who needed to cooperate.

The real “System 2” was in the informal negotiations between sales teams and research teams, the reciprocal favour-bank I mentioned in the SYDN post, where the amount of marketing time available was divided up. It required a bit of time and effort, but not too much, and when it didn’t deliver the right results, management were able to step in.

Informal systems like these are an important part of Stafford Beer’s system; they can often be greatly improved simply by reminding people that they exist, and encouraging managers to get in a room and talk to each other.

My experience of the resource bargain has left me rather cynical. Devolving decisions to the level best capable of making them comes into fashion when it's necessary to cut resources. One there's a surplus, the top levels find that the need for the organization to act as a united entity trumps such concerns.

One of the issues in many UK business cultures is that "getting in a room and actually talking to each other" seems to violate more taboos than one would ever expect on paper.