maths becomes metaphor

economics versus cybernetics, part two

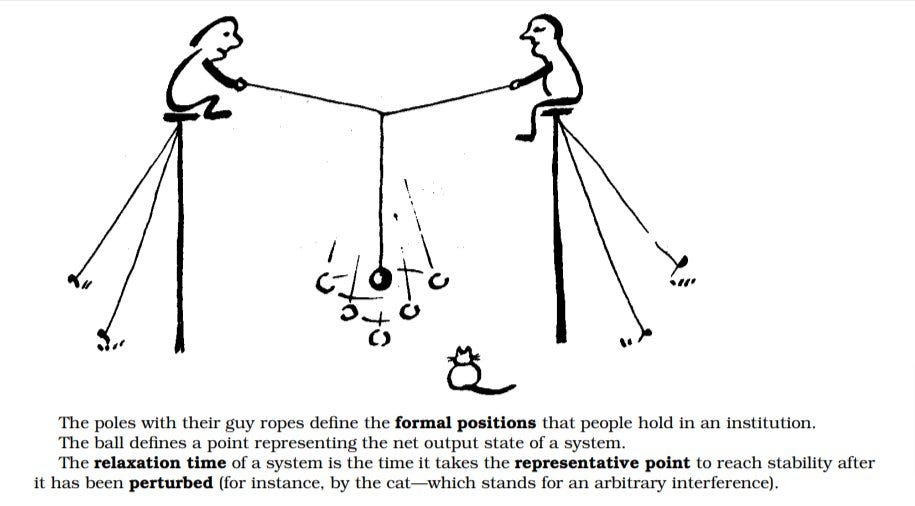

This continues from Wednesday’s post, which grew too long because I foolishly copied out Stafford Beer’s description of “homeostasis” (the management cybernetics equivalent concept to “equilibrium”), rather than just using this lovely cartoon, also from “Designing Freedom”.

You can see that the tennis ball in the picture has an equilibrium state, which it would eventually reach if everyone stayed stock still. You can also see (particularly given the presence of the cat) that it’s never actually going to reach that equilibrium state, and that in fact the stability of the system is going to depend on the resourcefulness and responsiveness of the two stylites. I think it matters a lot that economics thinks in terms of equilibrium rather than homeostasis …

…but a reasonable objection to me so far would be along the lines of “does it, though?”

After all, economists aren’t exactly unaware that markets involve buying and selling. Implicitly, their concept of equilibrium is actually one of homeostasis. (Someone very cleverly pointed out to me that in “Lying for Money” I had said that “fraud is an equilibrium quantity” when of course it’s a perfect example of homeostasis between fraudsters and prevention, which often shifts state in response to changing conditions. I was only beginning my cybernetics journey then, but it’s interesting that “equilibrium” was the word I reached for despite, I think, not being at all unclear about the actual concept).

So I think anything that you can do mathematically with the engineering/medical concept of homeostasis, you can do with the economics/physics concept of equilibrium. There are plenty models with multiple equilibria, “sunspot equilibrium” and game theory has even given us Hollywood movies about the development of equilibrium concepts based on tension between opposing agents.

But there’s a difference between what you’re able to do and what you can actually do. Different kinds of language are better suited to doing different things, as any computer programmer will tell you.

Which brings me back to the original Santa Fe connection. In a chat before the cybernetics session, Ben Recht made a comment that passed me by in the moment because I was too fixated on getting ready for my own bit. He pointed out that there’s a strange shift that takes place in all the control sciences as the system gets more complicated - you “shift from math to metaphor”.

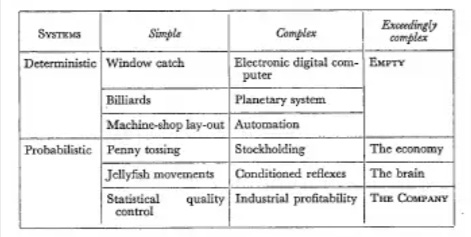

Stafford Beer identified a similar issue in 1959 (“Cybernetics and Management”, one of his first books and before the development of his main model). There’s a transition which happens as the system gets very complex; it becomes absolutely impossible to write down a system of equations to describe it, let alone solve the equations. So although you know (or at least, strongly believe) that the maths still works, you can’t actually do the maths any more. You’re left using the same concepts, but metaphorically; based on your knowledge and understanding of how the model works in tractable applications, you can think about its likely behaviour and rule things in or out.

As you can see “The economy”, “The brain” and “The Company” are all together in the bottom right hand corner, while “Industrial profitability” is in the middle column. You could also probably put “Mobile phone spectrum auctions” in that middle column too, and maybe even “Fiscal policy in recession”. But at some point, the dividing line has to be drawn. Things move from “complex” to “extremely complex”, and the mode of discussion changes from maths to metaphor.

At which point, the language you use is always threatening to become a mental prison. If you’re thinking in terms of equilibria, you might not pay enough attention to the way in which the equilibrium is reached, the balance of forces or whether the information-processing task is one that can’t succeed in practice. If you’re thinking in terms of homeostasis, you might not pay enough attention to where the system is ultimately headed, or whether the goal is feasible.

At its root, “The Unaccountability Machine” is me trying to say that we need a different set of metaphors to talk about our problems. I don’t think I necessarily realised that when I started writing it.

I think this is spot on - pre-1945 economists did think about equilibrium as the limiting point of some causal process, but as equilibria began to be described using increasingly complicated mathematics, they gradually gave up on describing the adjustment process, partly because it became hard to do so with the same level of mathematical sophistication. The result is that modern economics absolutely does think in terms of equilibrium without describing any process which reaches an equilibrium state, except perhaps in a handwaving fashion. If you'll forgive the self-promotion I have a recent paper about the problems with this (which incidentally cites this 'stack on p30!), very much in the spirit of Fisher's book: https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr1093

The post leads me to recall an old book by MIT's Frank Fisher titled, "Disequilibrium Foundations of Equilibrium Economics." This was his attempt to apply the maths to the pths taken outside of equilibrium.